Why slower is sometimes smarter

Rethinking Speed and Accuracy in Agility Training.

Ever had your dog fly off the a-frame or dogwalk, just missing the contact zone? Overshoot a turn? Take off early for a jump and knock a bar? These are all examples of the same underlying concept at work: the delicate balance between speed and accuracy in movement.

Understanding this relationship, what motor control and learning scientists call the speed–accuracy trade-off, can help us make smarter decisions in training. It’s not just about fixing mistakes. It’s about giving dogs the opportunity to learn how to move with intention, confidence, and clarity before we ask them to do it at full speed.

How Movements are Learned

When your dog performs an obstacle, they’re relying on what researchers call a motor program; an internalized plan for how to move their body to achieve a goal. These programs are developed over time through practice and feedback. They start off shaky and inconsistent, but become smoother and more automatic as the dog starts to understand how the task works under a variety of conditions.

But when we rush to full-speed performance before the dog truly understands the task, the result is often messy, fragile behaviour. The right reps matter more than just more reps.

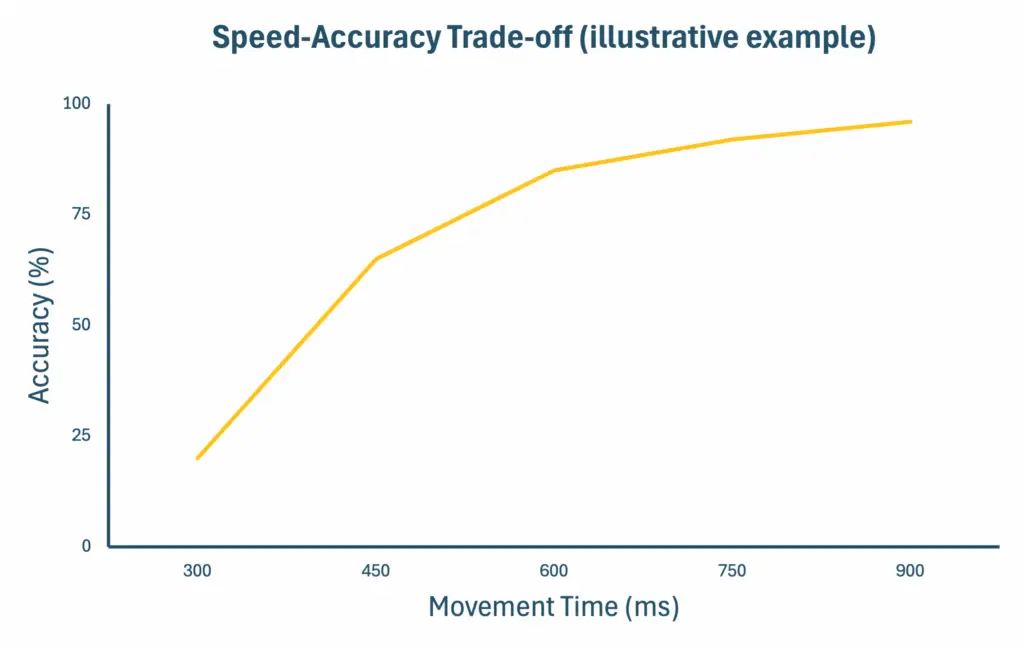

Understanding the Speed–Accuracy Trade-Off

In the 1950s, psychologist Paul Fitts described a now-classic finding in motor control and learning: the faster you try to move, the less accurate you tend to be. Known as Fitts’ Law, this relationship shows that the time it takes to complete a movement depends on both the distance to the target and the size of the target. In short: harder targets (small or far) take longer to hit if you want to hit them accurately.

This matters in agility. For example, when a dog is moving at high speed toward a contact zone, we expect precision will hold. But speed introduces variability, and variability introduces error, especially if the motor program isn’t well-established yet.

It’s not that people deliberately start with speed. It’s that they often introduce it too soon, long before the dog has clarity about what accurate performance actually looks like. If we want dogs to move fast and accurately, research tells us we need to start by training for accuracy first, then gradually increase speed while preserving that form.

In classic motor learning studies, groups trained for either speed or accuracy were later asked to switch goals. The accuracy-trained group was able to increase their speed over time while maintaining precision. But the speed-trained group struggled to regain accuracy—even with extended practice. This asymmetry tells us something critical: when we prioritize precision early on, we build motor patterns that are stable and adaptable. Speed can be layered in later. But when we chase speed too soon, we risk reinforcing inconsistent or imprecise patterns that are harder to refine down the road.

A Note on Spatial and Temporal Accuracy

In movement science, accuracy is often divided into two categories:

- Spatial accuracy: Where the movement lands. Did your dog’s feet hit the target zone?

- Temporal accuracy: When the movement happens. Was the cue timed well? Did the movement occur at the right moment relative to the rest of the sequence?

Both forms of accuracy matter in agility. But research tells us that speed tends to interfere more with spatial accuracy than temporal accuracy. When arousal is high and motion is fast, landing in the right place becomes more difficult than simply staying in rhythm.

In my training, I account for this by building a higher standard of performance accuracy early in the process. I assume that speed (and spatial and temporal interference) will degrade performance to some degree. So, I design our early reps to create stability and clarity, giving the dog a solid foundation to return to, even when the picture becomes more complex.

Applying the Trade-off to Contacts

When it comes to contact performance, trainers have developed a range of strategies (e.g., stride regulators, contact mats, visual targets, etc.) to help dogs consistently meet contact performance standards. One widely used convention is to encourage rear foot hits low in the yellow zone with visible separation between feet. While this pattern aligns well with natural running strides and is relatively easy for judges to see and call accurately, it’s not the only pattern dogs may use.

Front foot hits can also be successful, but they can be harder to spot, and sometimes less stable when dogs are under speed and stress. If we could just say, “So Spot, your job is to touch the yellow zone,” training contacts would be a lot simpler. But unlike humans, dogs can’t just be told what the goal is… they have to figure it out through experience and reinforcement. That makes understanding in the early stages essential. Before we add speed, we need to be sure they truly understand the task. Our job is to help them develop movement strategies that are both reliable and flexible, that hold up under pressure, even when the picture changes.

How I’ve Used These Concepts in My Own Contact Training

In my own training, I’ve experimented with ways to give dogs a clearer picture of what success looks and feels like, before introducing speed. One early tool? A mousepad. It became my first contact mat; a small, tactile, and consistent visual target placed low in the contact zone on the a-frame or dogwalk.

I didn’t focus on which foot hit. I wanted my dogs to confidently self-organize, regardless of approach angle, lead leg, or exit path. Instead of training a specific stride pattern, I focused on building adaptable motor programs that could hold up under the varied conditions dogs actually face in sport.

I also don’t ask my dogs to perform the full obstacle early in training. This isn’t just about the speed–accuracy trade-off (which is important). It’s also about the changing forces and balance demands involved in different phases of the obstacle. On the a-frame, the dog ascends, clears the apex, and begins descent. On the dogwalk, they transition from incline to flat top to decline. These shifts challenge postural control and dynamic stability, especially at speed or when cueing complexity is introduced too early.

These postural changes increase the physical challenge, and when paired with an incompletely learned skill, the risks aren’t limited to missed contacts. Accuracy can suffer, but so can safety.

I’ll explore this more in a future post: how changes in force and balance shape performance, and how we can support dogs as they learn to manage those demands.

Things to Try or Consider

This isn’t a checklist or formula. It’s a collection of ideas I’ve found helpful, and maybe you will too. If you’ve read this post on building technical skill, you’ll recognize some of the same themes here.

Start with Accuracy

Start with accuracy-focused sessions before layering in speed or complexity. This gives your dog time to build a stable motor program.

Use Visual Targets

Use a mat or tactile marker to clarify the target area early in training. These can fade later but offer helpful structure in the early reps.

Backchain the Obstacle

Backchain the obstacle, starting from the descent at full height. This builds postural strength and task clarity at low speeds before layering in approach skills.

Vary Exits Early

Practice with a variety of exit behaviours — turns, straight lines, and side changes. Train for accuracy first, then add speed.

Record Sessions

Use video to evaluate performance breakdowns. It can help you identify whether issues are spatial (like foot placement), temporal (such as a mistimed stride adjustment), or rooted in incomplete learning under pressure.

Avoid reinforcing mistakes

Avoid reinforcing speed if accuracy is lost — clean reps matter. Set a standard early, and let that standard shape your criteria as you build.

Why It Matters

Most of us want efficient, confident, reliable runs. But getting there means more than putting in time. It means building movement patterns that hold up when everything else is changing: speed, surfaces, distractions, handler position. That takes more than repetition. It takes intention.

This isn’t about one “right” way to train. It’s about recognizing that how we start, shapes how things turn out. And that sometimes, the smartest way to get fast… is to start slow.

A Final Thought

This isn’t a formula… it’s a reflection of how I think about movement, learning, and what helps dogs develop lasting skill. It’s grounded in research, shaped by trial and error, and still evolving.

If you’ve found different strategies that work, or noticed something new as your training has developed, I’d love to hear about it.

This sport keeps all of us learning. 💛

No comment yet, add your voice below!